Many of the emigrant ships carried flammable cargoes as well as human ones. Fires were not unusual. This is the story of one of them.

|

| La Catastrophe du Volturno. Source: Le Petit Journal Supplément Illustré, 26th October 1913 (author's copy) |

In October 1913, only eighteen months after La Touraine was involved in the Titanic disaster, Commander Caussin and his crew took part in a sea rescue involving British, German, American and Russian vessels in a remarkable feat of international cooperation. Peter Searle has accumulated an astonishingly comprehensive database, the Volturno Data Pages web site The Burning of the Volturno. The database includes several pages on La Touraine. Use the index on Page 01 to navigate around the site. There is a good summary of the Volturno story on Wikipedia here. Other sources were Jan Daamen's excellent Volturno Ship Disaster site and the Pages 14-18 Forum page on La Touraine here.

Thanks to our scrap of newsprint from 1915, I found a different, French, perspective on the story of Volturno's fiery end. It came, appropriately enough, from Le Petit Journal of 15th October 1913. The source is the Bibliothèque Nationale de France's information retrieval engine, Gallica.

The article is in two parts, topped and tailed by a description of La Touraine's arrival in Le Havre and the survivors she carried - this will keep for another post. The major part of the article is based on Commander Caussin's report to CGT's agent in Le Havre. After a brief introduction, what follows is my translation of this section of the Petit Journal article in its entirety, odd repetitions and changes of tense included. I have taken the liberty of de-garbling the ships' positions, and have learned a good deal of nautical vocabulary, thanks mainly to Linguée.

The article has much in common with a piece in the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant of the same date, which you may find both translated into English and in the original Dutch in the Volturno Ship Disaster site here. However the Petit Journal piece has a lot more to say about La Touraine's part in the rescue.

Another, very similar, article on this subject was published in L'Illustration of 18th October 1913. This too has an emphasis on the horror, for the titillation of the readership. This article and a translation into English may be found on the Volturno Datapages, Page15, here. Several of the pictures in this post come from this publication. I was lucky enough to find a copy in excellent condition via Delcampe for €4.99 plus postage, thank you Mr "Gypsum".

A note on the second officer's name: throughout this article he is referred to as M. Rousselet; every other reference to him is under the name Rousselot.

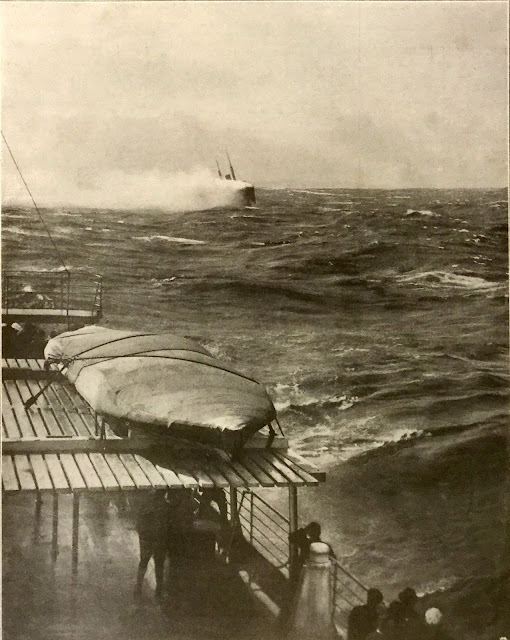

|

| Volturno from Carmania. Source: L'Illustration, 18th October 1913 |

For a complete description of events aboard Volturno, see the Wreck Report of the Board of Trade Enquiry "into the circumstances attending the fire which occurred on board the British steamship "VOLTURNO," of London, when in or near latitude 49° 12' N., longitude 34° 51' W., North Atlantic Ocean, on the 9th October, 1913, the loss of life which occurred, and the abandonment of the vessel on the following day". This makes riveting reading despite its unwieldy title.

The Wreck Report provides the introduction to the ship and the start of her last journey:

The "Volturno," Official Number 123737, was a British twin-screw steamship, built of steel at Glasgow, in 1906, by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Limited, and was registered at the port of London. ...She was a straight-stemmed vessel, had two masts, was rigged as a fore-and-aft schooner, and was of the following dimensions:Length from fore part of stem to the aft side of the head of the stern post, 342 feet.... Her gross tonnage was 3,602.22 tons, and her registered tonnage was 2,222 tons. ...

| ||

| Volturno leaving the port of Rotterdam, 2nd October 1913. Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Gallica) |

The "Volturno" having loaded a general cargo ... at Rotterdam and also embarked 22 cabin and 539 steerage passengers, sailed thence on the 2nd of October, 1913, bound to Canadian and North American ports, her draught of water being 17 feet 6 inches forward and 16 feet 7 inches aft. She was manned by a crew consisting of 93 persons, all told, and was under the command of Mr. Francis James Daniel Inch, who holds a certificate of competency as master, numbered 033893. Sailing as she did from a Dutch port, she was subject to the law of Holland as to emigrant ships. Before she sailed she was visited by the Dutch Emigration Commissioners who granted the requisite certificate for clearance testifying that she complied with the provisions of the law. She had also a British passenger certificate.

The report of the Captain of La "Touraine" recounts the scenes of horror aboard the "Volturno" and makes known the heroism of the French mariners.

Le Havre, 14 October.

In the report which he has addressed to the general agent of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique in Le Havre, Captain Caussin, commander of La Touraine, provides very full technical details of the fire and rescue of the Volturno. He expresses himself thus:

The distress signal

<<On Thursday 9 October at 8 o'clock in the morning, la Touraine being at 46° 58" N, 40° 59" W and heading on a course to the north 70° east, destination Le Havre, the wireless telegraphy operator informed me that the steamer Volturno was making a distress signal, asking for help and giving her position as 49° 12" N, 37° 11" W. The sea was, at this moment, high with a strong north wind. I immediately set a course toward Volturno making a 20° turn to port.

<<We were 205 miles from the Volturno and we could not hope to reach her before nightfall. The Carmania and the Sedlitz, very much closer than we were to the Volturno, were also making their way towards her. All day, we were kept in touch with events by the telegrammes exchanged between the Carmania, the Sedlitz and the Volturno. We heard the telegrammes from the Carmania and from the Sedlitz, but we were unable at first to hear the replies from the Volturno, which must have been working on batteries.

<<At 8:30 we learn that the Volturno is on fire. The Carmania asks if the fire is gaining, if they can fight it, if they can make steam and make way ahead. Carmania hopes to reach her at about 12:30 pm, her intention is to heave to and pick up the boats.>>

Captain Caussin relates that the Volturno had, as we know, put to sea two boats of passengers which have been lost from sight. The other dinghies that she has tried to lower to the furious waves have been destroyed. Then came the arrival of the Carmania, all of whose rescue efforts are crippled by the tempest; the Sedlitz and the Grosser Kurfürst appear in turn. The three ships make several attempts to save the victims, still without result, while on the Volturno the bridge explodes and her wireless telegraph stops working.

At 9 in the evening, la Touraine is in sight of the stricken ship which looks like a glowing inferno. Captain Caussin continues thus :

<< I see there is some possibility of putting a boat to sea, but not wanting, in such a grave circumstance, to rely solely on my own evaluation, I call the officers together and ask their opinions. Everyone considers that the whalers could be put to sea, but not the big dinghies, which would be demolished in launching them. >>Aboard La Touraine they ready themselves for the rescue

<<At 10:30, we take up station upwind of the Volturno and we heave to. It was at this time that some of the ships already present consider the weather to be sufficiently manageable to send boats. The Grosser Kurfürst notifies all the ships to be aware that she has boats out. The situation at this moment is the following: seas heavy, most of all for the boats; swell enormous and many waves breaking; wind strong from the North; moon and night fairly clear. The Volturno afire, her stern elevated; the bow and amidships no more than an inferno. Everyone is crowded at the stern. The six ships gathered there are hove to or manœuvring into the wind.The commander of la Touraine comments that the sheer number of ships coming together in that spot in itself constituted a danger. Then he comes to the departure of his first team of rescuers.

<<I make the decision to man a whaler and we make arrangements accordingly.>>

The brave men !

<<I am eager to draw attention to the heroism of the officers, the petty officers and the seamen crewing the boats. During the entire duration of the operations, the sea was enormous for the boats. The swell remained very great and many waves were breaking. Those who were preparing to leave the ship were ready from the outset to make the sacrifice of their lives.

<<When it came to selecting the crew of the whaler, many came forward. We were spoiled for choice. We picked the crew and M. Rousselot, second captain, was keen to take command and to set off. All the crew had put on lifebelts and all took their places in the whaler, without hesitation and with a courage one can only admire for there was certain danger in confronting the sea in such conditions.

<<At a favourable moment, the whaler was swung out. A catastrophe nearly occurred when she touched the water, caught by a wave. She was slammed violently against the side, and was surely going to break up and sink. At last, she could get away and moved off to the applause of the passengers.

<<It was 10:45 at night and we had arrived on the scene at 10:30. We watched the whaler as she struggled painfully against the sea and, at times, vanished completely in the troughs of the waves. Then we lost sight of her, her lantern having gone out.

<<Once the whaler had left, I took up station at another location for La Touraine in order that the whaler would not have to come back against the sea and I was positioned to the west of the Volturno. The wind and the sea coming from the north, we decided to bring out another boat. M. lzenic, first lieutenant, claimed the honour of taking command.

<<The crew was recruited with the same ease as the first time. Everybody embarked with the same courage and the same sang-froid. The whalers put to sea successfully in spite of the identical difficulties. We saw for quite some time her lantern which had managed to stay alight.

| ||

| The Volturno from Carmania, rescue under way. Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Gallica) |

<<After some time, when we judged that the boats were likely to be coming back, we started to flash the gauntlet [ceston] (the Company signal) at the stern and to sound the horn, the sound of which is quite distinctive and recognisable. La Touraine, all night, remained hove to and immobile in the same place, side on to the wind, in the swell and rolling from side to side, with a few lulls. Several of the ships in the vicinity appeared to have sent boats and were making signals of encouragement. Others did not send any.>>How the first survivors were picked up

<<At 1:30 in the morning, on the 10th we sighted the lantern of a boat, making its way towards us, and soon a whaler came alongside, downwind on the port side: it was M. lzenic's. We had put out the fenders, the pilot ladder, mooring lines, slings and everything needed.

<<With much difficulty, taking advantage of a lull, but in spite of that being hurled against the side, and risking at every instant to be smashed and engulfed, the whaler managed to come alongside. She contained five passengers who succeeded with much trouble in getting aboard using the pilot ladder, after first having been raised in a sling.

<<M. Izenic came on board and gave me an account of the rescue.

<<The outward journey had been gruelling and the night made it even more difficult. At every instant, the whaler risked being overturned by mountains of water that they could not see coming; she was half swamped and it was necessary to bail continually.

<<On coming up to the Volturno, the spectacle was frightful. All the fore and middle of the ship was no more than an inferno. The ship was rolling and pitching enormously.

<<The passengers and crew had taken refuge right at the stern and there was an uninterrupted clamour of terror.

<<It was only possibly to come alongside at the stern, and still with the greatest care, because with the hammer blows of the ship pitching, they were threatened by being crushed under her hull.

<<The intention of M. Izenic was to stand off at some distance from the ship's side and pick up those who jumped into the sea wearing their lifebelt, but no one from the Volturno was willing. Besides, the whaler was jammed willy-nilly against the hull because of the way the ship was drifting. Immediately she was invaded by the passengers who lowered themselves down by means of ropes, or simply jumped into the whaler. Two were killed in this way and disappeared under the stern of the Volturno. Another fell onto one of the men in the boat who received minor bruises. It is fortunate that M. Izenic had to pull away at times from the side, for the whaler would have been invaded, and since she could only carry a small number of men, she would inevitably be swamped.

<<Five passengers were brought on board. M. Izenic had seen M. Rousselot's whaler which was standing off at some distance. M. Rousselot called to the men to jump into the water. There was no other boat.

|

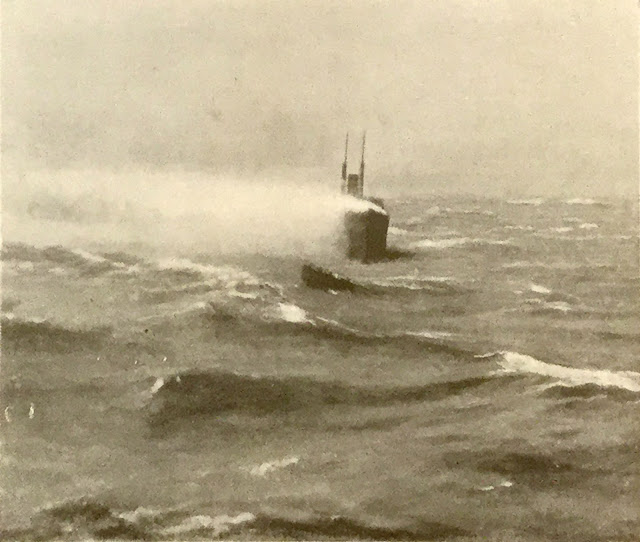

| Volturno from Carmania. Source: L'Illustration, 18th October 1913 |

<<M. Izenic's return was beset by the same difficulties as the outward journey. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the boat was more heavily loaded; finally, she was able to come alongside La Touraine. M. Izenic and the men were completely drenched but wanted to set off again. I preferred to change the crew. Volunteers came forward in great number. Bo'sun Coute took command of the whaler and she left for her second voyage.

<<The sea conditions stayed much the same. Once the passengers were on board, they were handed over to the doctor and the purser, placed in cabins and given all necessary care. They were in a very weak state, both physically and emotionally.

<<At 1:45 in the morning, we sighted M. Rousselot's whaler; she had come alongside with the same difficulties and they had succeeded in taking on board three passengers.>>The launch of a big dinghy is attempted.

<<The crew was changed. M. Rousselot wanted to set off again and soon the whaler was on its way. I was unable to exchange more than a few words with M. Rousselot. I wanted at that point to try to send a big dinghy which was capable of carrying more people.

<<The launch was very difficult, but the sea, while remaining very high for a boat, had moderated a little. Profiting by this improvement and a lull in the rollers, the dinghy was launched.

<<M. Le Baron, second lieutenant, asked to take it out. The crew got aboard full of ardour and the dinghy set off. We were hoping for a good result. Sadly, at 4:30 in the morning, the dinghy came back having been unable to pick up anyone.>>

<<The two trips to and fro had been very hard, and once at the Volturno, M. le Baron concluded that the dinghy was too heavy to manoeuvre and not handy enough to clear the stern and avoid being caught under the hull. M. le Baron witnessed an accident to one rescue boat. This boat was caught under the hull at the stern as Volturno pitched, and was flattened. The men had, nevertheless, managed to get free and swim to another boat. I learned later that this boat belonged to the Minneapolis. M. le Baron therefore had to content himself with standing off at some distance shouting and making signals to the people on the Volturno to jump into the water, but nobody dared, seeing which M. le Baron came back to switch boats.

<<At 3:30 in the morning, bo'sun Coute's whaler came back with seven passengers, along with the second captain's whaler with seven passengers. The passengers were brought on board successfully, and, as the wind was freshening again and the sea was rising, I requested the party to defer the rescue operations until daybreak.>>After paying tribute to the skill of bo'sun Coute [?Coadou?], Captain Caussin includes the moving story of rescue related to him by M. Rousselot, the second captain, who did the work of ten with admirable devotion.

<<M. Rousselot>>, he said, <<states that the Volturno, in drifting, created a dangerous eddy, pulling the boats along her side into a perilous position, putting them at risk of a smash, or being overloaded with passengers, leading to the same outcome.

<<After several attempts to get close, M. Rousselot stationed his boat toward the stern, a little downwind, and paid out two circular lifebuoys fitted with lines. These buoys drifted along the ship's side. They called to the passengers to take to the water, but nobody dared. Some of the survivors dropped into the water; they were picked up in the night.

The shipwrecked people throw themselves into the sea. They are picked up in the night.

<<After repeating this trial several times, without success, M. Rousselot taking advantage of a sudden moment of calm between two squalls, came as close as possible without compromising the safety of the boat and spun out the lifebuoys once more. Three men, this time, threw themselves into the sea, but, after some hesitation, hung on to the lifebuoys. The whaler was able to pick them up and get away. The crew of the whaler was exhausted after several hours of continuous effort. M. Rousselot set course for La Touraine, where he arrived still fighting an enormous sea. The passengers hoisted aboard, the crew changed, recognition signals and lanterns loaded, and M. Rousselot returned to the Volturno.

<<Profiting by the presence of La Touraine's second whaler commanded by bo'sun Coute, M. Rousselot placed his craft downwind abeam and plunged towards a boat hoist and some haul-lines, from where some passengers, seeing him coming, proposed to slide. Immediately on arriving under the lines, a veritable hail beat down on the whaler. The frightened passengers were throwing themselves from all directions onto the men in the whaler and onto M. Rousselot, trapping the oars and putting the whaler in great danger, tipping her down by the bow to the point of taking on water over the gunwale. M. Rousselot, judging the situation to be hopeless if anyone else tried to come aboard, only had time to push off and took the other whaler in tow; these two boats had drifted and were abeam to the fire; the smoke caught the throat; cinders were falling on all sides; the heat was intense.

<<Finally, after half an hour of exhausting effort the two boats were able to get out of Volturno's backwash. M. Rousselot, finding his whaler overloaded for the sea conditions, transferred seven men to the other boat and the two whalers set a course in company to return aboard La Touraine. The return journey was particularly perilous, the boats being fully loaded and the sea having risen it was necessary to bail out continually the water that was coming on board.

<<Finally, after much effort, the two whalers came alongside at 3:30 in the morning. The passengers were brought on board successfully and the whalers were hoisted, ready for the morning. M. Rousselot had seen, close to the Volturno, some boats from the other ships which likewise were unable to come alongside.>>

|

| Volturno from Carmania. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France |

<<At daybreak, about six o'clock, all the ships present moved in on the Volturno. La Touraine did the same. I headed into the wind and the two whalers were sent, commanded by M. Le Baron and M. Royer, 3rd lieutenant, at their request.

<<It continued to be with the same difficulties and in danger of their lives that the rescuers were able to set off and reach the Volturno.

<<I then manoeuvred to put the ship downwind so as to be able to pick up the whalers when they returned.

<<M. Le Baron came back with two women and ten children, and M. Royer with eight passengers. The transfer of the passengers to the Volturno was performed, this time, with a little less difficulty, first because it was daylight, also because the panic was less, each seeing that the ship was holding together and help was on its way.

<<The women and children had been rescued by sling, the ships on station had also sent boats. The Grosser Kurfürst and the Czar which had the good fortune to be able to approach very close to the Volturno, having arrived first, made a number of trips. I would have been able, as well by night as by day, to send a greater number of light boats, but I feel that the risks were too great and I did not want to expose too many people to those risks at the same time.>>

|

<<La Touraine's whalers therefore made another journey, but nobody was left on the Volturno. we therefore wanted to ascertain exactly what had become of the two boats from the Volturno that had vanished, loaded with survivors, in conditions which revealed what a panic reigned.The captain ends his report by proposing certain officers and men of la Touraine for awards. It will be noticeable that in his report, Captain Caussin is silent on what concerns himself but in the opinion of all the passengers, officers and crewmen, he too conducted himself in heroic fashion.

<<If there had been less panic, more people would have been saved. It is certain that many people must have drowned in the night, judging for example by the two men killed before Mr Izenic's eyes. If the crew and the passengers had kept a cool head, everybody might have been saved.

<<The doctor, the purser and several officers were the last to disembark. The captain was the last to leave.

<<At 8:30 la Touraine withdrew from the vicinity of the fire, along with other ships, after saluting the wreck. The Carmania signalled that she was going to explore to the north to try to find the Volturno's two boats.

<<In these conditions, I thought it was preferable that we should not all make for the same place, and I explored to the south until 10 o'clock. Judging it to be useless to carry on searching any longer and unhappily being only too certain that the boats must have been overwhelmed and there was no hope of finding them, I resumed the route for Le Havre.

<<La Touraine, in these rescue operations, held honourable rank given her late arrival and the impossibility of her taking up station as close to the Volturno as she would have wished, the best places being occupied by the first to arrive. In the presence of British, German, Russian and American ships, the French mariners behaved brilliantly and held high and strongly the honour of the French flag.>>

|

| Part of the rescuing fleet, although not La Touraine, which had two funnels. Source: L'Illustration, 18th October 1913 |

As anticipated, there were awards for his crew. They received the Sea Gallantry medal from King George V of England, and the Prix Henri Durand (de Blois) from the government of France. The biggest prizes, as seems appropriate, were awarded to those who took command of the lifeboats, and Caussin himself later became Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur. Source: la Bibliothèque nationale de France (Gallica).

|

| From Journal officiel de la République française. Lois et décrets, April 1914: Gallica. |

The commentary reads:

After such an experience, what a shock it must have been at 2am on 6th March 1915 when the fire alarm sounded on La Touraine herself....

"Rescue of 42 persons from the English steamship Volturno, 10th October 1913 - during the night of 9th to 10th October, in the North Atlantic, in very severe weather, two whalers from the transatlantic liner Touraine succeeded, in extremely perilous circumstances, in saving 42 people from the English steamer Volturno, aboard which an immense fire had broken out.

Informed at 8 in the morning of the 9th October by telegraph of the situation aboard the Volturno, Naval Reserve lieutenant Caussin, commander of Touraine, was heading for the vessel, which was 205 miles away.

Touraine arrived at the location of the fire at 10 in the evening, and succeeded, in spite of immense difficulties, in deploying her two whaler lifeboats.

The seas were very heavy, with a strong swell and northerly gales; the whalers risked at any moment being swamped by the massive seas or wrecking while alongside the stricken vessel.

At a cost of a thousand efforts, after each of them made three trips, the two whalers succeeded in bringing on board Touraine a total of 42 people, between 10.45 pm and 7am.

It required the skill, the sang-froid and the courage of the crew to bring about the rescue of 42 persons in such difficult conditions."

After such an experience, what a shock it must have been at 2am on 6th March 1915 when the fire alarm sounded on La Touraine herself....

1 comment:

A terrific read. Bravo once again! As ever, I am amazed by the number of people one can cram onto a ship.

Post a Comment